This is the sixth entry of a ten-part blog series celebrating the Lab’s 10th anniversary. The series shares insights and lessons learned over the past decade, exploring practical knowledge from accelerating climate finance solutions in emerging markets. See all entries here.

August 20, 2024

When we submitted the Climate Adaptation Notes (CAN) to the Global Innovation Lab Climate Finance (the Lab) in 2020, adaptation to climate change was a relatively new focus area for investors. Funders and governments were increasingly emphasizing resilience, and CAN aimed to support adaptation projects in the water sector. We saw an opportunity and were thrilled to be selected for the Lab’s inaugural Southern Africa program.

The timing seemed perfect. Two years after Cape Town’s “Day Zero” crisis, when the city had nearly run out of water, the country was alert to the critical threat of water scarcity. The office of the President of South Africa had also just established an infrastructure committee to identify projects for development over the next decade. We thought this would provide fertile ground for us to identify water infrastructure projects for CAN.

However, we soon faced hurdles in the project pipeline. While we initially relied on a government-sourced list of over 200 infrastructure projects, the impact of COVID-19 combined with short-term political priorities resulted in slow progress or stagnation for most on that list. Still today, very few have been implemented. Consequently, the implementation of CAN has been delayed.

It has been frustrating, but our journey with the Lab has brought valuable lessons that can inform future climate finance innovators and ensure a stronger foundation for their projects. Despite CAN’s challenges, its core structure remains relevant and implementable, with strong potential to catalyze blended finance.

With the adaptation finance gap widening, CAN offers a valuable blueprint for others working to mobilize private investments for much-needed sustainable infrastructure with a focus on climate adaptation.

CAN's financial structure: leveraging South Africa's strengths

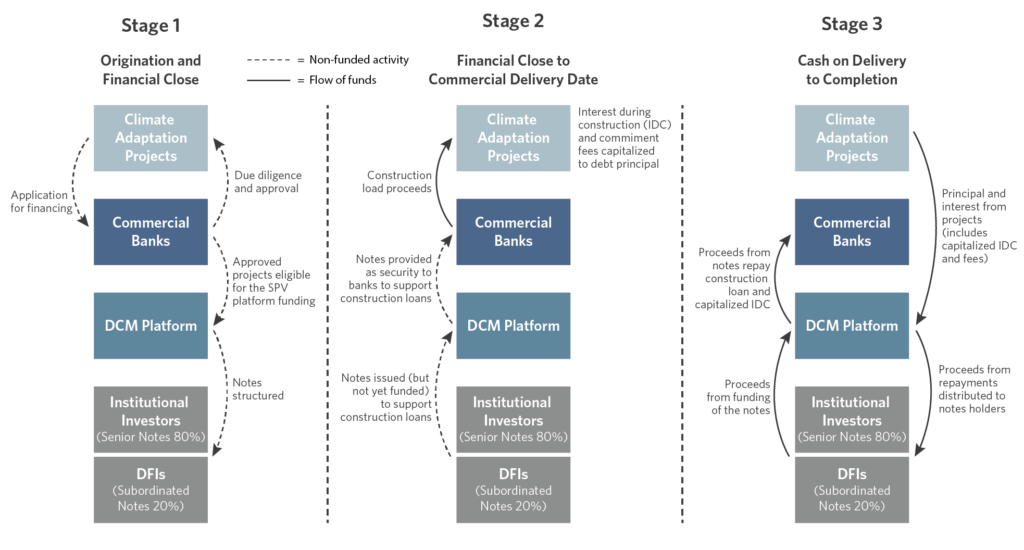

CAN’s financial structure aimed to capitalize on several South African debt capital market strengths. While adaptation projects typically face greater funding challenges than mitigation ones, significant development finance was available on concessional or risk-mitigation terms for water infrastructure projects in the country. In addition, South Africa’s estimated USD 400 billion in gross domestic savings are a vast potential pool of finance.

However, these funds have gone largely untapped for infrastructure projects. Despite this massive pool of money, a significant portion remained unused for infrastructure projects. This was further exacerbated by stricter liquidity rules under Basel 3, making long-term bank loans more expensive due to increased capital provisioning requirements.

We planned to leverage development finance to mitigate the risk for institutional investors. Subordinated notes provided by the development finance institutions (DFIs) would act as a buffer, absorbing potential losses before impacting the senior notes purchased by institutional investors.

By doing so, CAN could bridge the gap between two distinct markets: short-term bank project finance and longer-term institutional investment.

The project pipeline challenge: A lesson learned

Amid the widespread failure of water infrastructure across South Africa, there is a growing need for investment in refurbishment, upgrades, and new wastewater treatment plants. In 2023, the city of Durban’s water treatment system collapsed, leading to beaches being closed due to contamination with sewage water. Similar challenges with water treatment systems have recently plagued Johannesburg.

We identified 30 to 40 suitable adaptation projects for CAN from the list of infrastructure projects published by South Africa’s Infrastructure Office. Some of the most obvious applications involved water treatment and reuse. For example, Cape Town had identified the need for several billion rands worth of new water treatment plants to avoid most of the city’s water being “flushed” into the sea.

CAN’s potential here was clear. It could finance a network of wastewater treatment plants along the coastline to capture this unused water, treat it, and reintroduce it into the system. This approach would have sustainably addressed a critical water scarcity issue.

We trusted the efficacy of this list, assuming that the majority of the projects had reached the “bankability” stage. Unfortunately, our optimism didn’t translate to reality. For various reasons, primarily political, most of the listed projects either stalled or never materialized. We simply couldn’t find a concrete infrastructure project to tailor CAN to.

This experience highlights a crucial lesson: the importance of robustness in the project pipeline. While we believe in CAN’s structure and approach, its success hinges on securing a suitable project for implementation. The lack of a reliable pipeline prevented us from moving forward.

Looking back, we could have been more critical in evaluating the initial project pipeline. Relying on a government infrastructure list turned out to be insufficient. Ideally, we should have conducted more thorough due diligence on each project rather than assuming its validity because of its inclusion on the list.

Another crucial lesson is early engagement with potential funders. Once a promising structure is developed, testing it with funders is essential. While potentially discouraging, negative feedback allows for early adjustments before significant resources have been invested.

Global applicability of CAN

While CAN has faced implementation challenges in South Africa, its potential remains strong. The core structure offers a valuable tool for financing climate adaptation projects in suitable markets. The core concept is not unique to South Africa and can be adapted for broader application.

Looking forward, CAN could be applied in other middle-income country markets that share key characteristics, including:

- Well-developed domestic capital markets.

- Large domestic savings pools.

- Established banking infrastructure.

For example, Brazil, Indonesia, and India all possess these features, making them strong candidates for CAN.

While my involvement might not be feasible for implementation in these specific countries, CAN’s beauty lies in its open-source nature. The Lab makes the instrument structure freely available without any intellectual property restrictions. Therefore, any entity could consider CAN as a financing tool for climate adaptation projects, provided it has the necessary financial market infrastructure and, of course, a secured pipeline of projects.

Check out the entire Lab 10th Anniversary blog series

1. Five strategies to break down barriers to private climate investment

2. How a well-designed theory of change guides clearer social and environmental modeling

3. Building a compelling investment case for climate finance instruments

4. Making the most of concessional capital: The Lab’s blended finance approach

5. Enhancing the appeal of small-ticket investments with Sustainable Energy Bonds in India

6. Why Climate Adaptation Notes didn’t take off – and the lessons I learned

7. How Brazil’s Green FIDC became the Lab’s champion for private investment mobilization

8. Adaptation finance: Six key steps for structuring instruments that deliver results

9. Beyond box-ticking: Why gender-responsive climate finance is effective climate finance

10. Emerging trends, opportunities, and challenges in climate finance

BONUS: A decade of the Lab: Finding a balance between climate finance and actionability (24 September)